Dewey Square, Project Story

Dewey Square fronts South Station, New England's most important multi-modal transportation center. In addition to South Station, several commercial buildings and The Federal Reserve Bank define Dewey Square. The reconfigured Square sits over the submerged interstate—known as the Central Artery—which replaces the elevated highway that formerly snaked its way through downtown Boston.

Author(s)

Machado Silvetti

Published

August, 2015

Dewey Square Headhouses in Downtown Boston

History

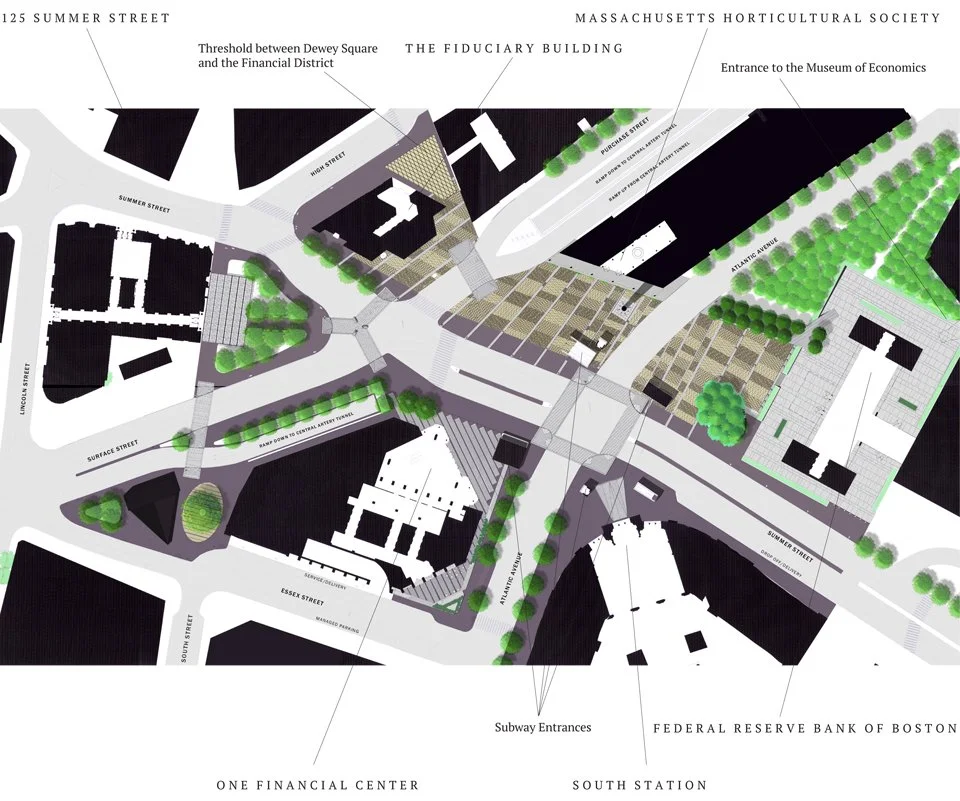

The area in which Dewey Square is located had traditionally been an industrial district—primarily for the production of leather, garments and printing, as well as general warehousing. A portion of modern-day Dewey Square was originally underwater and was the site of a number of shipping piers. The size of this new district rivaled the dimension of the traditional city core. Our design expanded the scope of the previous plan to include the sizeable, privately owned plazas that abut the square, and re-conceived the entire area as one urban space with a single contemporary character unique within the city.

1903 photograph of South Station

By 1984, the fundamental and immensely liberating ideas on which post-modernism as a critical endeavor rested had been corrupted, misunderstood and consumed enough to produce a common building styling that covered the land from coast to coast. The professions of development planning and landscape design were also affected by these events.

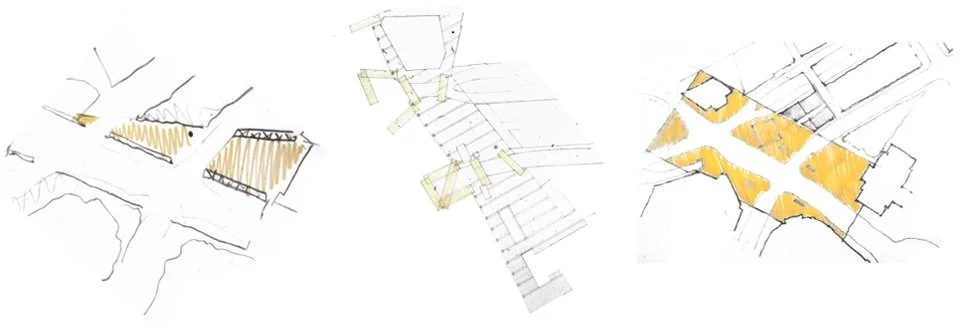

Initial sketches by Jorge Silvetti

Central to this state of architecture was a fascination with "things European", with an urbanism of "fabric and monuments", with "the campanile and the clock", with "gates and parterres", "the pitched and the pedimented", "the Chippendale Skyscraper", etc. More importantly, with this affair came the concomitant distrust of the American city, a disregard for the building types that culture and the market had produced and that were not yet "brought into architecture"; a discomfort with the infrastructures that organize our cities, with the "parking lot and the mall", and with a myriad of built facts that characterized American urbanity.

Thus, it became pretty obvious then that Architecture needed to engage itself with the late 20th century American city, catch up with its design demands and respond with an array of new building configurations, even with new types.

The Big Dig

Officially known as the Central Artery/Tunnel Project, the Big Dig reconnected downtown Boston with its waterfront neighborhoods and the historic North End. It was the most complex and expensive highway project ever undertaken in the United States. The city replaced outdated highway infrastructure with a new state-of-the-art highway system, most of which is underground or underwater. The eighteen-year, eleven billion dollar project consists of two major components: the new eight-to-ten-lane underground expressway and the extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike from what was its current end-point south of downtown Boston, through the Ted Williams Tunnel, to Logan Airport. Five major new highway interchanges and a two-bridge crossing of the Charles River were also planned on being built.

Diagram of the Artery Project

Restoration of the surface followed with landscaping and three quarters of the space became open. The remainder was dedicated to modest commercial and residential developments. There was much debate about who would control the development of these parcels and the open space and who would maintain and program the open space once it was built. Dewey Square was the first in a series of important public spaces planned over the submerged Artery, finally culminating in what is known as the Rose Kennedy Greenway.

Dewey Square Master Plan

Unlike the kinds of master plans that rely on simplistic "big" visions (but ignore the realities of American property ownership and real estate market issues in existing cities), the Dewey Square Master Plan acknowledges the real issues facing the design and development of public space in American cities. What our process proposes is neither true public space (difficult to program or maintain adequately with the decrease in government spending) nor entirely privatized "public" space (well programmed and maintained but contaminated with the squeaky clean artificiality of commercial interests).

The proposed plan took a realistic approach to the subsurface conditions of the Artery Project and the renovations underway on the subway station. Street-level activity was programmed by activating all of the edges of Dewey Square and streets leading into the Square. These edges are defined by street-level retail uses. Pedestrian experiences were carefully choreographed from the existing city fabric to Dewey Square and vice versa.

Site model showing found objects

Featured objects mediate at different scales in the square. Smaller-scale elements in the proposal negotiate between the enormous scale of the buildings that surround the Square and the scale of an individual person. In attempting to maintain the space as a distinctive, inclusive, and progressive public plaza, the proposed guidelines promote a condition of orchestrated variety through several components.

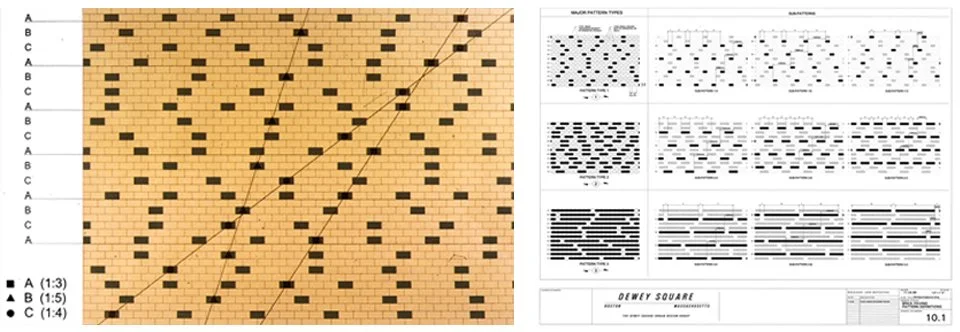

Pavement Pattern

The paving pattern was designed to be seen obliquely. Budget criteria meant that the project team had to consider brick and/or precast concrete unit pavers for the majority of the paved surfaces.

We took this constraint as a challenge to create a paving strategy that would work successfully when viewed from a variety of distances. The resulting paving pattern was as successful to the pedestrian crossing the Square as it was when seen as a more abstract pattern visible from the thirty-first floor of a neighboring highrise.

POV Analysis and Representation

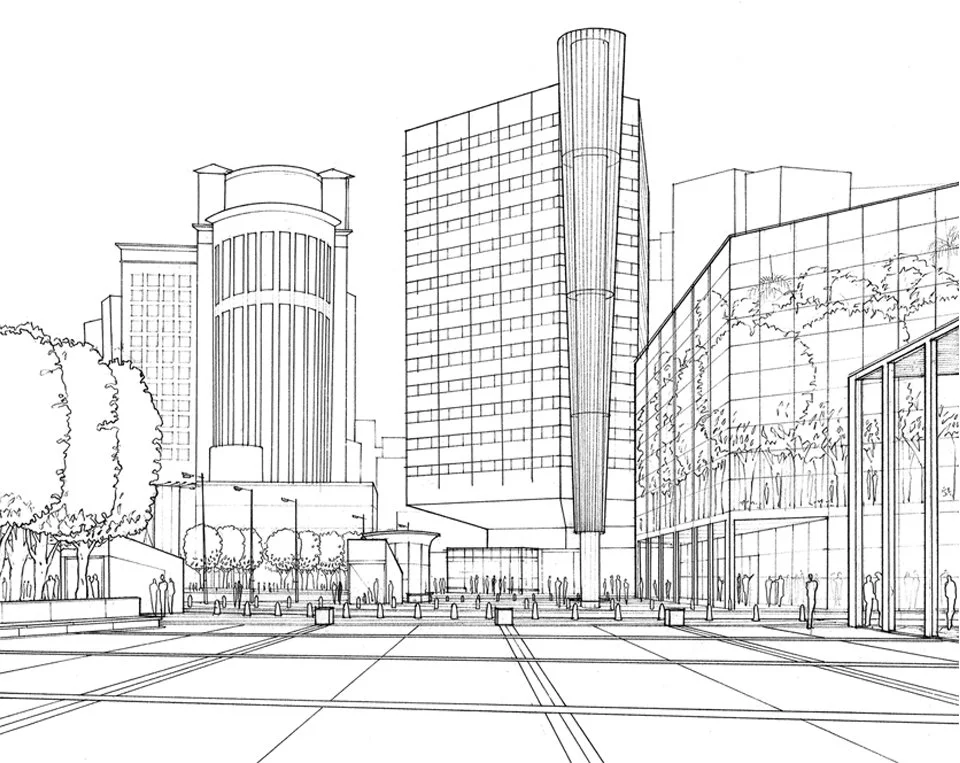

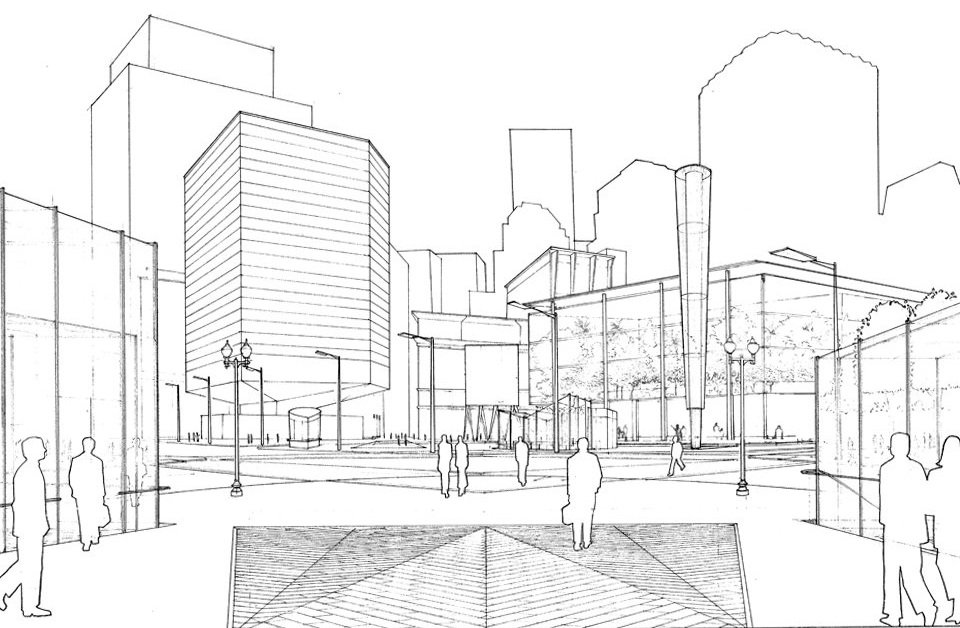

Specific decisions were made about the disposition and character of the elements that make up the physical context of Dewey Square by testing their intended effect on pedestrians and motorists. The most effective tool to analyze and convey these intended effects, are a series of perspective views, constructed from specific station points in the plan.

The Massachusetts Horticultural Society holds the northern edge of Dewey Square

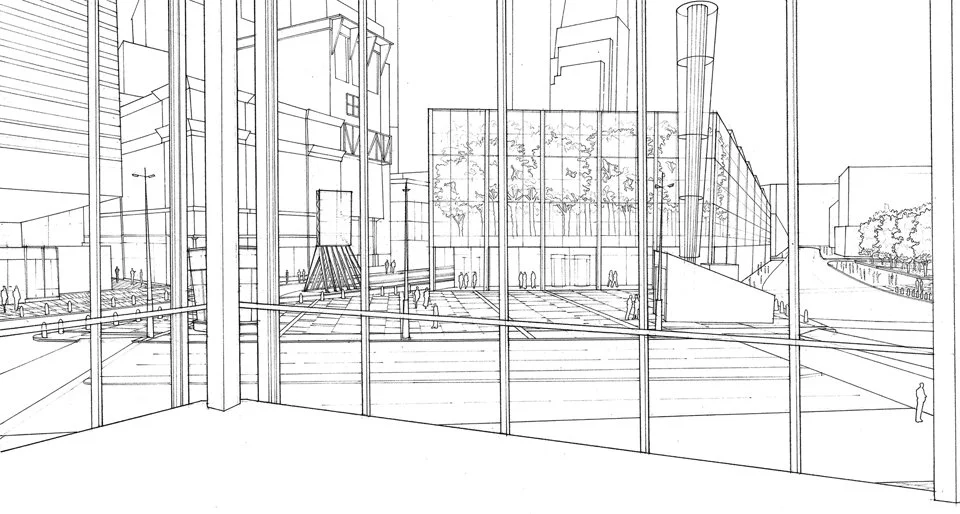

Looking at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society from the lobby of One Financial Center

Walking out of South Station

"Machado Silvetti has an extraordinary ability to work successfully with community groups and public agencies... In the Dewey Square process Machado Silvetti demonstrated tremendous intelligence in accurately analyzing the challenges and opportunities in this complex and formless part of town, talent in interpreting the physical and political context to create a workable and very beautiful plan, and skill in managing the debate among the working group members with dramatically different agendas, by keeping the focus on good design."

Robert Kroin, AIA, Former Chief Architect, Boston Redevelopment Authority

Food trucks at Dewey Square

Related Content

-

The design for the Dewey Square precinct in Boston’s Financial District expands the scope of the previous plan to include the sizeable privately owned plazas that abut the square, and re-conceives the entire area as one urban space with a single contemporary character unique within the city. Read more about the full project here.

-